A Biblical Case for LGBTQ+ Inclusion in the Church…From Paul, Part 1 (Circumcision)

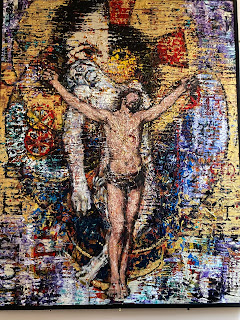

Photo by Michelle Bonkosky on Unsplash

“How can you ignore the Bible?” Any pastor, or Christian for that matter, who has voiced support for full inclusion of LGBTQ+ persons has probably receiving this stinging question (or one similar) at some point. I have heard such on many occasions and it always hurts, at least a little. As a pastor, every sermon that I preach is grounded in the Bible. My ministry is part of the long tradition of biblical exegesis, reflection and practice. My life has been shaped by a growing relationship with the writings of the Bible.

I suppose it is easy to prematurely claim people who support full inclusion of LGBTQ+ persons are ignoring the sacred texts. There are a few passages in the Bible that speak negatively towards certain same-sex practices. Many biblical scholars have cast doubts on these so called “clobber” passages by pointing to historical context, ancient and contemporary understandings of human sexuality, as well as appropriate translations of particular Greek words. Still, these complex arguments are often disregarded or minimized by those who perceive the stark clarity of the clobber passages.

In this article, though, I argue that inclusion does not have to begin with neutralizing the clobber passages. Rather, the Bible itself makes a strong and compelling case for inclusion. While the clobber passages indeed must be considered and dealt with if we are to be responsible Biblical interpreters, they are relatively few, sporadic and must be read within the larger themes of the Bible.

This approach to interpreting Scripture through its greater themes is one used by Jesus. He was regularly criticized for disregarding particular scriptural prohibitions, or at least interpreting them in a way that demonstrated God’s compassion and inclusion was a higher priority than strict obedience to legal mandates. Examples of this include healing on the Sabbath, blessing Gentiles like the Syro-Phoenician woman, and associating or eating with sinners and outsiders. It wasn’t that Jesus ignored the writings of the Hebrew Scriptures (Old Testament), rather his lens for interpreting them was God’s inclusion and compassion. He drew on the larger themes of the Hebrew Scriptures.

This way of approaching scripture carried over into early Christianity. Interestingly, one of the strongest voices for a greater inclusion was the apostle Paul. While it is true that a select few passages from Paul’s writings have been used to argue against LGBTQ+ inclusion , these select passage are overshadowed by Paul’s greater emphasis that God is doing a new thing and all people who place their faith in Jesus Christ are invited to participate in the saving work of God. Three major themes across Paul’s writings reveal his interpretation of inclusion: circumcision, Gentiles, and the Holy Spirit.

This article, broken into a series of three parts, will explore these themes. Part one, this installment, deals with Paul and circumcision. Part two explores how Paul understands God including Gentiles into the redeeming work of Christ. The last installment, part three, takes a look at Paul’s understanding of the Holy Spirit at work. It finishes with a few concluding thoughts on how Paul’s treatment of these themes informs our understanding around the inclusion of LGBTQ+ persons in the life of the church today. We begin here, though, with Paul and circumcision.

Circumcision

Much like Jesus, Paul’s critics accused him of ignoring the letter of Scripture in favor of a more spiritual understanding. This led Paul to write such things as, “…our competence is from God, who has made us competent to be to be ministers of a new covenant not one of letter but of the spirit; for the letter kills, but the Spirit gives life.” (2 Corinthians 3:5b-6, NRSV) Further the criteria for justification, according to Paul, is not in strict adherence to Laws and traditions, but rather by having faith/trust in the saving work of Jesus Christ. (Galatians 2:15-16). All people, Jews and Gentiles, will be brought into God’s healing grace in Jesus through faith, or deep trust in God. Like Jesus, Paul prioritizes inclusion through faith over strict adherence to isolated passages of scripture.

This point of view was perhaps most tested for Paul with the question of circumcision. In Genesis 17, the patriarch Abram (soon to be Abraham) learns that God promises to make him the “ancestor of a multitude of nations” and that the covenant will be everlasting. For those who were part of God’s covenant people, the sign of inclusion would be circumcision for men, boys, infants and even servants in the household. Uncircumcision, then, equated to being outside God’s covenant: “Any uncircumcised male who is not circumcised in the flesh of his foreskin shall be cut off from his people; he has broken my covenant.” (Genesis 17:14, NRSV). Note that Genesis clearly states a person must be circumcised “in the flesh”.

This is where it gets difficult for Paul. While he and other Jewish men were circumcised, Paul was an apostle to the Gentiles, the uncircumcised. It seems many of his converts were not inclined to participate in the painful ritual, thus putting them at odds with the clear direction of scripture. To deal with this dilemma in a credible way, Paul has to address both Abraham and the practice of circumcision itself.

Paul takes up the question of Abraham in Galatians and Romans. In Romans 4, Paul argues that Abraham received God’s promises only because he first trusted, had faith, in God. Faith, then, is a better entry to the covenant than circumcision simply because it came first. Circumcision, which came after faith, was of secondary importance. Circumcision was simply a seal of the faith that Abraham previously demonstrated. It was not a prerequisite for inclusion into God’s promises.

In Galatians 3 Paul takes a slightly different approach. He notes that in Genesis the promise is given for Abraham’s “offspring”, singular, and not plural “offsprings”. The plural would seemingly refer to all of the circumcised Jewish people who came after Abraham. Paul argues, though, that the singular use of “offspring” is a reference to Christ, not the Jewish ancestors of Abraham. Christ is the priority and the one who fulfills the promise of Abraham. Thus, all who have such faith in Christ will be welcome into God’s saving work because faith/trust is the criteria for inclusion, regardless of circumcision.

This leads to circumcision itself. Leaning on a spiritual interpretation, Paul states that “real circumcision is a matter of the heart-it is spiritual and not literal.” (Romans 2:29) He understands that there are many people who are physically circumcised who do not live by the Jewish laws and there are also uncircumcised people who are very faithful. Therefore, true circumcision is a matter of the heart, not the body. It is spiritual. In essence, the Gentiles are welcome into the saving work of God, even though they have not been circumcised in the flesh as scripture commands, because they have put their faith/trust in Christ.

Through both Paul’s treatment of Abraham and circumcision, he interprets the scriptures in favor of inclusion. He rejects more strict interpretations of Abraham and circumcision that would have limited God’s grace to a smaller group who closely followed the letter of scripture. Instead Paul favors a reading that is more open and makes a way for Gentiles who trust in Christ to be included amongst the people of God, as well.

Stay tuned for part 2 (Gentiles) and part 3 (the Holy Spirit) of this article…

Comments

Post a Comment